By Geneive Abdo

Iran Analyst, The Century Foundation

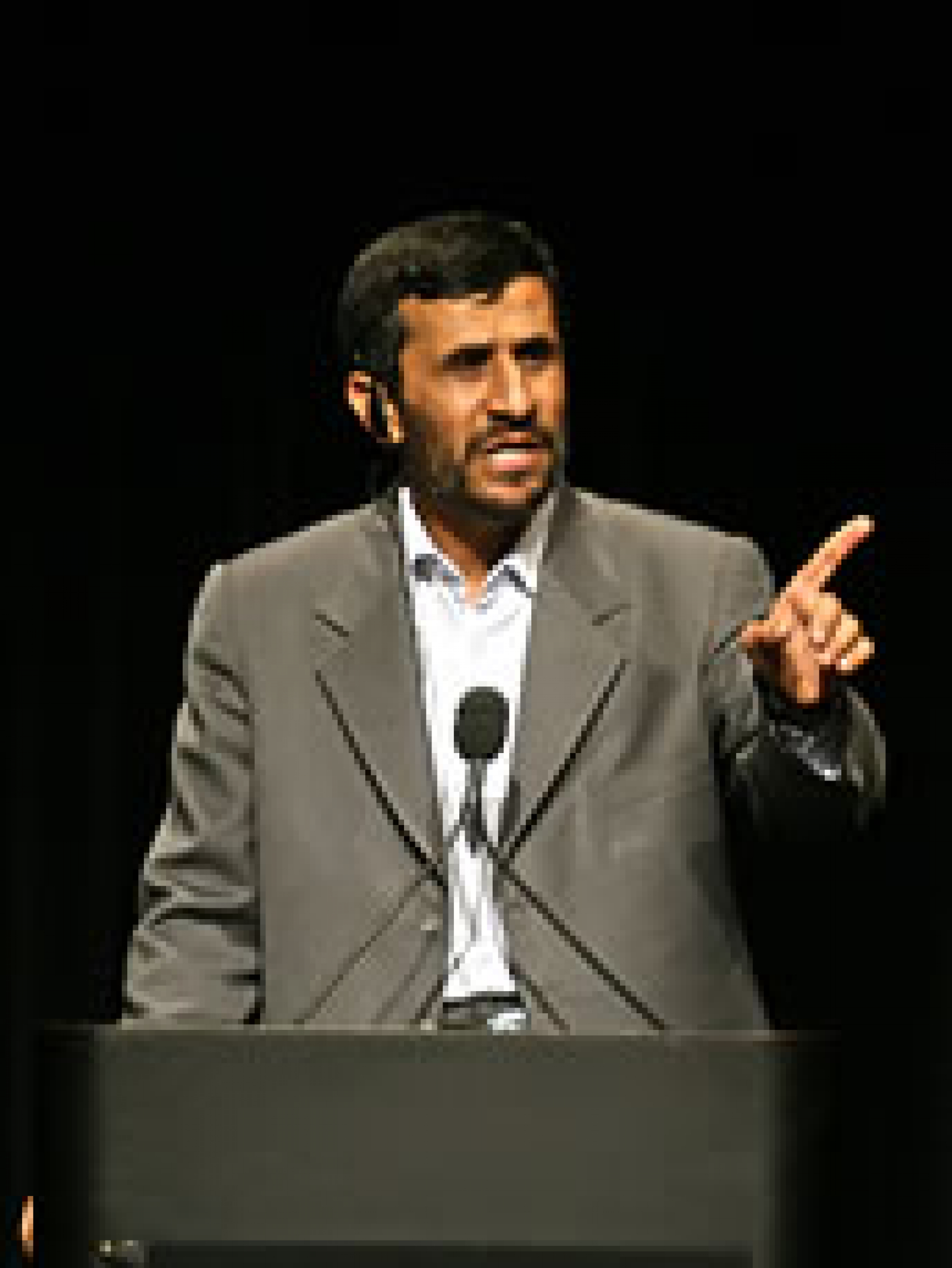

In the midst of the worldwide furor over Iranian President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad’s speech at the United Nations World Conference Against Racism in Geneva, the international community overlooked the fact that his remarks were not targeted toward a Western audience. They were directed at his Iranian constituency at home and his newfound supporters in some countries in the Middle East, stretching from Egypt to Lebanon. His scripted performance before a crowd vehemently opposed to his views inspired the exact response he desired. Shortly thereafter, Iranians and key groups in the Middle East came to his defense. In solidifying his electoral base in Iran while also expanding his popular support in the region, Ahmadinejad is making a strong case before Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei and other hard-liners that he should be re-elected in the June presidential poll.

Ahmadinejad, who at the April 20 conference continued his familiar refrain of accusing Israel of being a “totally racist, cruel and oppressive regime” and the West of using the Holocaust as a “pretext” for the Palestinian occupation, is considered a role model not only for Hezbollah and Hamas, but for millions of others in the Arab world who are disenchanted by U.S. and Israeli foreign policies in the region. Ahmadinejad’s regional influence is particularly useful, as he confronts a coalition of leading pragmatic conservatives in Iran who believe his rhetoric has made Iran a pariah in the West and, as a result, are making international relations a key campaign issue in the upcoming presidential election.

Demonstrating their support for Ahmadinejad’s confrontational speech, 200 Iranian parliamentarians in late April issued a statement applauding his performance at the UN conference and condemning the more than 20 foreign representatives who walked out in protest. The United States, Israel and seven other Western governments had already boycotted the event over concerns that Israel would be singled out for condemnation. “A man from the Islamic and revolutionary Iran … has attended the conference and has uncovered the appalling face of modern criminals including the Zionist regime and its supporters. We, as representatives of the Iranian nation in the Majlis, announce our all-out support for the firm and committed stance of our president,” the parliamentarians said in their statement. First Deputy Speaker of Parliament Mohammad-Hassan Abou-Torabi-Fard and Economics Committee Chairman Mesbahi Maghaddam went a step further, saying that foreign governments also support Iran’s position as “justice seeking.”

In the Arab world, popular figures echoed support for the Iranian president. Syrian Foreign Minister Walid Muallem said at a press conference that a large portion of Arab public opinion supports Ahmadinejad’s views. And Hamas media advisor Azam Tamimi told the Islamic Republic News Agency (IRNA) that Ahmadinejad stood out in front of Arab leaders in expressing what every Muslim should be saying about Israel and the Palestinian occupation. Even though many Arabs do not favor Iran’s theocratic state, they believe it stands as a great symbol against Western domination and the Palestinian occupation. Since Ahmadinejad was elected, he has used these issues as trademarks of his presidency to win worldwide attention. In recent weeks before the April 20 speech, he appeared to have toned down his blistering rhetoric, after President Barack Obama expressed a willingness to end 30 years of hostility with Iran. But the UN speech demonstrates that Ahmadinejad believes he benefits politically from his confrontational approach to the outside world, and has no plans to abandon it.

Praise from the parliament, other Iranian government officials and Arab activists stood in stark contrast to the response from Mir-Hossein Mousavi, one of Ahmadinejad’s reformist rivals for the presidency, who called the speech “a disgrace, the scandal of Switzerland.” Mousavi’s views represent those of other prominent reformers, including former President Mohammad Khatami, who have argued that Ahmadinejad’s re-election will cement Iran’s isolation from the international community. While Mousavi agrees with Ahmadinejad on some issues, including Iran’s right to advanced nuclear technology, he disagrees with his hostile rhetoric.

The divide between reformists and the pragmatic conservatives vying against Ahmadinejad and his hard-line supporters reflects not only the fierce internal fighting in Iran over the Islamic republic’s international relationships, particularly with the West, but also Iran’s position in the world. Ahmadinejad and his fellow hard-liners believe Iran should be a regional superpower in the Middle East and that this can be achieved by representing Arab views on foreign policy issues – even at the expense of a possible rapprochement with the United States. In fact, they believe dialogue with the United States and better relations with European governments undermine Iran’s strength in the region. Considering Iran’s growing political power through its proxies Hamas and Hezbollah, its influence in Iraq and within some other Sunni Arab societies, hard-liners believe now is the moment Iran has been waiting for ever since the 1979 revolution.

By contrast, Ahmadinejad’s political foes believe Iran has become too isolated since his election in 2005. They believe Iran should use its new-found strength to rehabilitate the country in the eyes of the West, not only for political gain, but more importantly for economic benefit. Iran is in the throes of the worst economic crisis to hit the country since its war with Iraq in the 1980s. With tougher international sanctions looming as a result of Iran’s commitment to enriching uranium and advancing its nuclear program, reformists and pragmatic conservatives believe better relations with the West could avert further economic penalties.

As the June election draws near, the question is, which view will prevail? Throughout Iran’s post-revolutionary history, political power has shifted more often between hard-liners and pragmatic conservatives than between conservatives and reformers, who rarely have had much influence inside the state structure. Although Ahmadinejad has appeared vulnerable at times to fierce criticism from pragmatic conservatives, his speech at the UN conference is evidence that he believes his hard-line rhetoric will serve him well both inside and outside Iran.

During his 2005 campaign, Ahmadinejad emphasized his desire to inaugurate the “third Islamic revolution” and return the country to a climate of revolutionary fervor. The first revolution came in 1979 when the Shah was ousted and Ayatollah Khomeini returned to Iran, and the second, he argued, occurred with the seizure of the U.S. embassy in Tehran later that year. During the four years of Ahmadinejad’s presidency, he has encouraged a return to an earlier period of revolutionary ideology within Iran’s domestic and foreign policy agenda. Ahmadinejad’s re-election or defeat will be a signal whether Iran’s core leadership believes in the “third Islamic revolution” or seeks a slightly different path to Iran’s role in the world.

–

Published on May 8, 2009