Figure 1

SHARE

It is no longer news that disinformation is a global challenge. We’re flooded with deceptive and manipulated content in every sphere of our lives.

One of the most alarming impacts of disinformation is the threat it poses to democracy worldwide. People need access to reliable, authentic information to exercise their democratic rights and responsibilities, and governments need credible feedback on their policies and performance to meet their obligations to citizens. Disinformation undermines these critical processes.

At this point there are many competing theories on how best to combat information manipulation. These approaches fall into a variety of categories, depending on whether they’re focused on disrupting the flow of disinformation, exposing it, or competing with it. Disruption tactics include regulating social media platforms, establishing norms and standards for online behavior, and blocking content or platforms. Exposure approaches include verification systems such as fact-checking and debunking campaigns, as well as labeling systems for “whitelisting” or “blacklisting” platforms or sources. Competition strategies usually involve government or corporate strategic communications efforts aimed at countering disinformation narratives. Similarly, support for independent media and media literacy efforts aim to promote the supply and consumption of information that’s reliable and authentic.

No one yet knows which approach -- or combination of approaches -- works best. But it’s clear that it’s not enough to fight byte for byte with disinformation attacks as they emerge. Disinformation is cheap to produce and ubiquitous. The purveyors of disinformation -- whether they’re states, businesses, organizations, or individuals -- will always have more resources at their disposal than those trying to combat it. This asymmetry requires that counter-disinformation strategies be strategic and evidence-based.

We do know that no single tactic is a “silver bullet” that will stop disinformation in its tracks or a “silver injection” that will inoculate all of us. Information environments vary across communities and evolve over time, requiring constant adaptation. We’ll need holistic approaches that build up the integrity of our societies so they’re resilient to the disinformation that will inevitably breakthrough.

We also know that it’s not enough for civil society and the private sector to do all of the heavy lifting on countering disinformation. Governments have major roles to play -- and not just in reducing the amount of disinformation that gets into the system, but also in building resilience to the assaults.

Through public opinion research NDI has conducted in Ukraine and Georgia, we believe we’ve identified a powerful yet under-appreciated counter-disinformation tool: good governance.

Ukraine

As high-stakes presidential and parliamentary elections approached in Ukraine in 2019, information manipulation was rampant. Disinformation narratives from Russian and domestic sources aggressively sought to discredit the electoral process, among other targets.

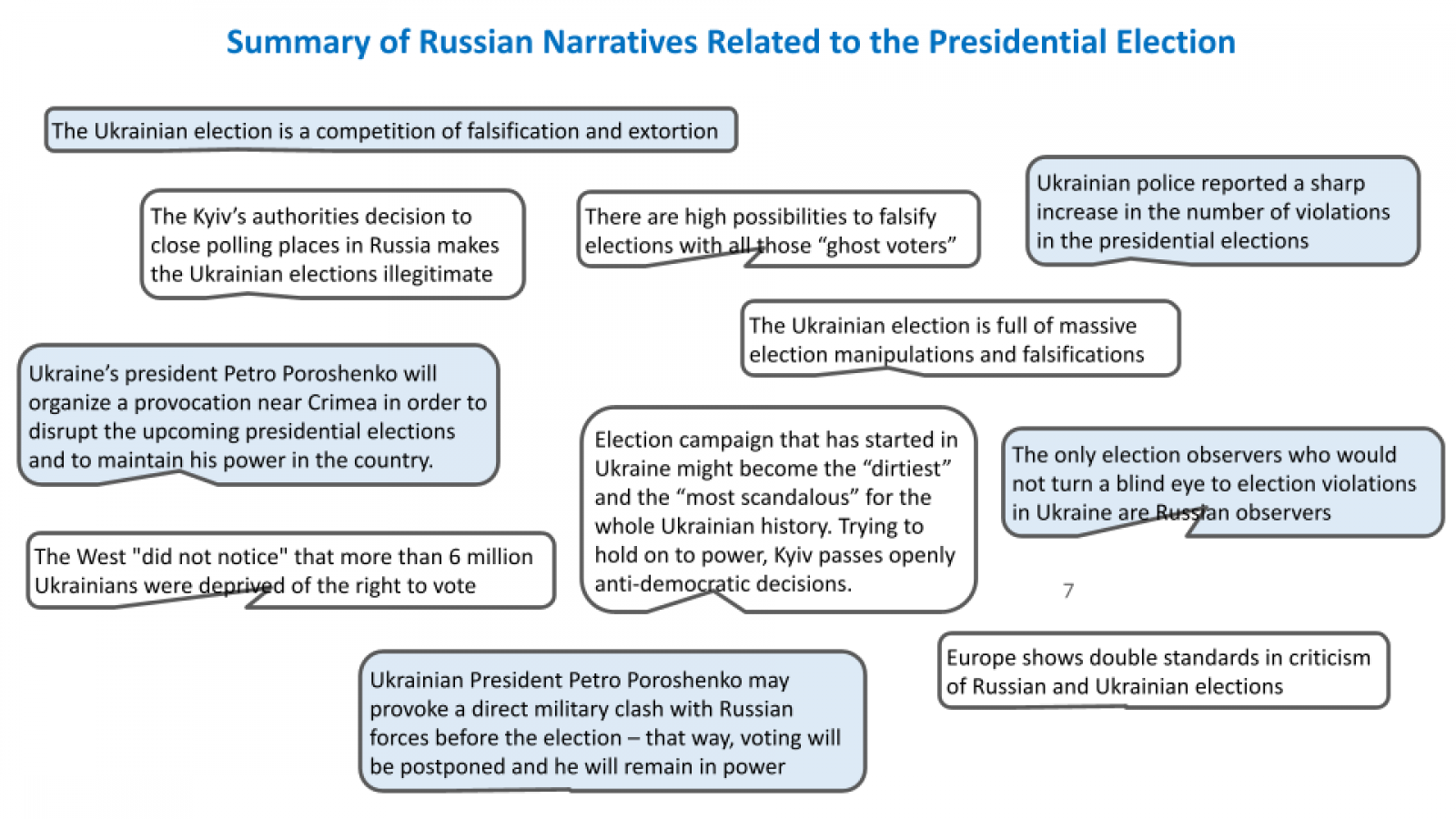

The narratives floating around Ukraine on traditional and social media involved allegations of falsification and extortion, “ghost voters,” provocations, predictions of six million Ukrainians being disenfranchised and characterizations that these were the “dirtiest and most scandalous” elections in Ukraine’s history (see figure 1).

These allegations were effective. During this time, NDI was conducting a series of tracking polls to assess trends in public attitudes (see figure 2). One of the questions the polls were asking was whether people would trust the official results of the elections. Not surprisingly, given the malign messaging, confidence in the election administrators and processes was low in the weeks preceding the March 31 presidential election.

However, as confirmed by credible election observers, including NDI and nonpartisan citizen monitoring groups, the election proceeded largely democratically. In a statement issued on April 1, the day after the first round of the presidential election, NDI said, “This election was genuinely competitive and voters turned out in higher numbers than in the 2014 presidential poll. For the second time since the Revolution of Dignity, despite ongoing Russian aggression, Ukraine held an election that broadly reflects the will of voters and meets key international standards.” Importantly, NDI noted that polling-station procedures, which are the election-related government functions most tangible to people, were sound: “On election day, voting, counting, and tabulation processes were largely peaceful and orderly. The Central Election Commission’s preliminary results were confirmed by a credible parallel vote tabulation conducted by the Ukrainian citizen association OPORA. Voter turnout was robust. Election officials and observers performed their roles effectively.”

After each round of the election, on March 31 and April 21 respectively, the tracking polls showed that confidence in the official results increased substantially, and we know from later surveys that these high ratings were sustained through the parliamentary elections in July (see figure 3).

We’re not in a position to prove cause and effect here, but it’s reasonable to consider that effective governance -- or, in this case, running democratic elections, which voters could see and experience with their own eyes -- neutralized the impact of the discrediting disinformation that was blanketing the country.

Georgia

Georgia provides another interesting case study. In late 2020 and early 2021, Georgia struggled with high covid infection rates, along with much of the rest of Eurasia, Europe and the US. Early in the pandemic, however, the government of Georgia was given high marks for effective management of the crisis. Georgia’s first covid case was registered at the end of February 2020. The government’s response was swift. By mid-March, all schools, universities and non-essential businesses were closed and public transportation was suspended. After the introduction of a state of emergency on March 21, large gatherings and intra-city travel were banned. There were nightly curfews and heavy fines for violating the state of emergency. “Stay at home” warnings were displayed at bus stops, and mobile phone operators broadcast safety messages to people’s devices. The government developed a one-stop website where one could get explanations and information, including in minority languages. The effort was led by the country’s top scientists at the National Center for Disease Control (NCDC). The scientists in charge became known affectionately as the “four musketeers,” reflecting their public popularity at the time.

As a result, by early July there had been only a thousand confirmed covid cases in Georgia, compared, for example, to neighboring Armenia, which had had 26 thousand by that point.

At the same time, the country was awash in covid-related disinformation that sought to confuse Georgians about the sources, seriousness of, and solutions to the virus. These included allegations that the European Union had abandoned its member countries in the fight against covid, that covid and various other biological weapons had been developed at a US-funded lab in Georgia, that the vaccine would contain microchips, and that Bill Gates had some kind of malicious involvement.

However, NDI surveys conducted between June 2020 and February 2021 have pointed to a couple of interesting findings. First, Georgians overwhelmingly credited the government and its public health experts (the four musketeers) with managing the crisis effectively (68 percent in February 2021). Seventy-three percent said the low spread and mortality rates were due to steps taken by the government and medical professionals (see figure 4).

Second, when asked which information sources on coronavirus they trusted the most, Georgians pointed overwhelmingly to medical professionals, the NCDC, and the government -- well ahead of the media, religious organizations, or NGOs, for example (see figure 5). The strong trust in these bodies was consistent across age groups, geographies, and even political affiliation, which is significant in a political environment as polarized as Georgia’s.

In other words, swift, transparent, and evidence-based government action on covid built public trust on that issue. Because the government was performing effectively on managing covid, its communications on the topic were able to cut through the fog of disinformation, and Georgians thus got better, more reliable information. These findings again point to the idea that good governance is a powerful counter-disinformation tool.

Next Challenge: Vaccine Hesitancy

As of spring 2021, the Ukrainian and Georgian governments -- like many others -- were shifting their attention to rolling out vaccines. As with all other aspects of the pandemic, vaccines have been the subject of significant information manipulation. Not surprisingly, NDI research found In late 2020 and early 2021 that roughly half of Ukrainians and Georgians were saying they would not get vaccinated. These figures point to the need for the governments to take swift, transparent and evidence-based steps to build public confidence around their inoculation efforts, making use of credible messengers, in order to deliver crucial services and safeguard public health.

Need for Further Exploration

The data shared here is more suggestive than conclusive. The Ukraine and Georgia surveys were conducted at different times and used different methodologies and questions, so they’re not directly comparable. Nevertheless, the findings provide some intriguing clues about the connection between good governance and countering disinformation. These questions merit further research.

It may seem self-evident to those in the democracy support community that effective performance leads to credibility, which in turn allows for meaningful, transparent, evidence-based communication and the ability to cut through disinformation. Yet when we scan government counter-disinformation strategies around the world, rarely -- if ever -- is “good governance” on that list.

It may be time for those in the counter-disinformation community to expand their thinking on what constitutes an effective strategy. Technical fixes, forensics, fact-checking, high-quality media, savvy consumers, and regulation have their roles. But we also need to be thinking about how to strengthen the body politic so disinformation never gets a chance to gain purchase.

Author: Laura Jewett is the Regional Director for Eurasia and Andriy Shymonyak is a Senior Program Officer for Eurasia.

NDI is a non-profit, non-partisan, non-governmental organization that works in partnership around the world to strengthen and safeguard democratic institutions, processes, norms and values to secure a better quality of life for all. NDI envisions a world where democracy and freedom prevail, with dignity for all.