SHARE

In early May, NDI sent a team to Benghazi, to meet with Libyans and assess what they will need for a successful democratic transition. Les Campbell, NDI director for Middle East and North Africa programs, writes about his experiences.

As we left the Benghazi airport headed toward the city, we passed two billboards that read, in English, “No Foreign Intervention. Libyans Can Do It Alone.” As it turns out, this is a purely symbolic sentiment that certainly doesn’t apply to democracy assistance. Over four days in Benghazi we met with more than 100 Libyans, and organized an impromptu workshop for new associations that are struggling to keep up with demands from citizens.

Once in the city, the billboards took on a more public-minded flavor, one reading, “These Public Properties Belong To All Of Us. Keep Them Safe,” and another, “We Have a Dream.” Off the main road, graffiti was the order of the day with the most popular phrase being, “F*#k Muammar” — self-explanatory, I think.

A common sentiment expressed in meetings was that organizations like NDI are late in coming. “Welcome, where have you been?” was the start to most meetings. While the Interim Transitional National Council (TNC) has already produced a number of very general draft papers on constitution writing, systems of governance and “democratic culture,” the groups with which we met requested expert advice on election systems, formation of a constituent assembly, political party development, civic education and a host of other issues.

Many of these meeting were facilitated by key Libyans who had participated in NDI regional programs in Malta, Morocco, the U.S. and elsewhere.

NDI Arabic language publications were highly popular. There is such a hunger for information that the fact that we have and are willing to supply Arabic language manuals on party organization, advocacy, principles of democracy, a glossary of political terms, federalism, decentralization, building an NGO, etc., causes absolute amazement. The isolation of this part of Libya was profound and what is going on now is a genuine awakening. We ran out of hard copies the first day so we copied the manuals onto flash drives and distributed them that way. It seemed like we bought out every flash drive in the city. We went to 12 stationary stores on our third day and couldn’t find another one to buy at any price.

At one meeting, a participant had printed and collated — at his own expense — six or seven of the manuals, including some that are 120 or more pages. He gave several to the TNC legal committee members because they are writing a temporary constitution. We’ve since made arrangements to ship in hundreds of NDI’s Arabic language manuals to individuals and organizations we met in Benghazi.

In addition to meeting with various TNC committees, we met with six former political prisoners, and found an almost insatiable appetite for discussions about democracy. We excused ourselves after two hours but not until after multiple invitations to dinner, to visit home villages and to address other gatherings. We were able to meet with the Benghazi Scouts, who are widely considered the biggest and most effective civil society group in Libya, but they are avowedly non-political. We discussed a civic education and youth leadership program modeled along the lines of a similar NDI program with the Algerian Scouts organization and they were intrigued.

We met with representatives of two women’s organizations and members of several youth organizations. We also spoke with a Facebook activist who called for demonstrations in January and was jailed for 10 days in February. There was an infectious energy among young people we met with to take action and contribute in any way they could — we met with a young woman who is working with her friends to launch a radio program to counter the propaganda of Libyan leader Muammar Gaddafi that it’s not safe for women to leave their homes in the east. Another youth association is working on food distribution and asked for our advice about how to build alliances with other emerging groups to reach more people.

An interesting theme that cropped up several times was the fate of regime supporters should Gaddafi fall. Most Libyans argue against what they see as the excesses of “debaathification” in Iraq but they clearly expect justice for the many victims of the regime. One possible solution discussed at NDI’s TNC meeting was the possibility of a South African-style truth and reconciliation committee.

Meeting with Libyans, especially in groups, is interesting. Their long history of repression and lack of access to the rest of the world means that individuals are appreciative of the audience and anxious to discuss their future. Despite, or maybe because of, long exposure to Gaddafi’s perverted form of “direct democracy,” meetings are a bit unfocused and there is surprising deference to people perceived to be superior in status. Every meeting was surprisingly civil — even in the larger groups, people patiently waited for others to make their points. Several people were emotional in meetings — welling up with tears about people killed since February and clearly moved by their new-found freedoms. Several remarked about the novelty of meeting in public to discuss political reform.

Interestingly, Gaddafi’s limited reforms since 2006 seem to have had the unintended consequence of creating a ready-made transitional government of technocrats. The Benghazi City Council members we have met as well as most members of TNC committees played a role in the fake reforms of the past few years. It turns out that many were fully aware the reforms were empty promises, and were biding their time until an opportunity for real change presented itself.

Under Gaddafi’s system, people’s committees labored for days, sometimes weeks, debating and discussing initiatives sent to them through government channels. These deliberations, often circular and unending, allowed Gaddafi and his closest cronies to make the real decisions. This model is the only one that Libyans have any experience with, and the challenge in the coming months and years will be to build transparent institutions, clearly delineated lines of authority and accountability mechanisms.

Related:

- Focus groups in Tunisia reveal young people’s hopes for democratic transition»

- Leaders in Chile’s democratic transition travel to Cairo»

- Algerian Muslim scout leaders inspire youth to engage in politics»

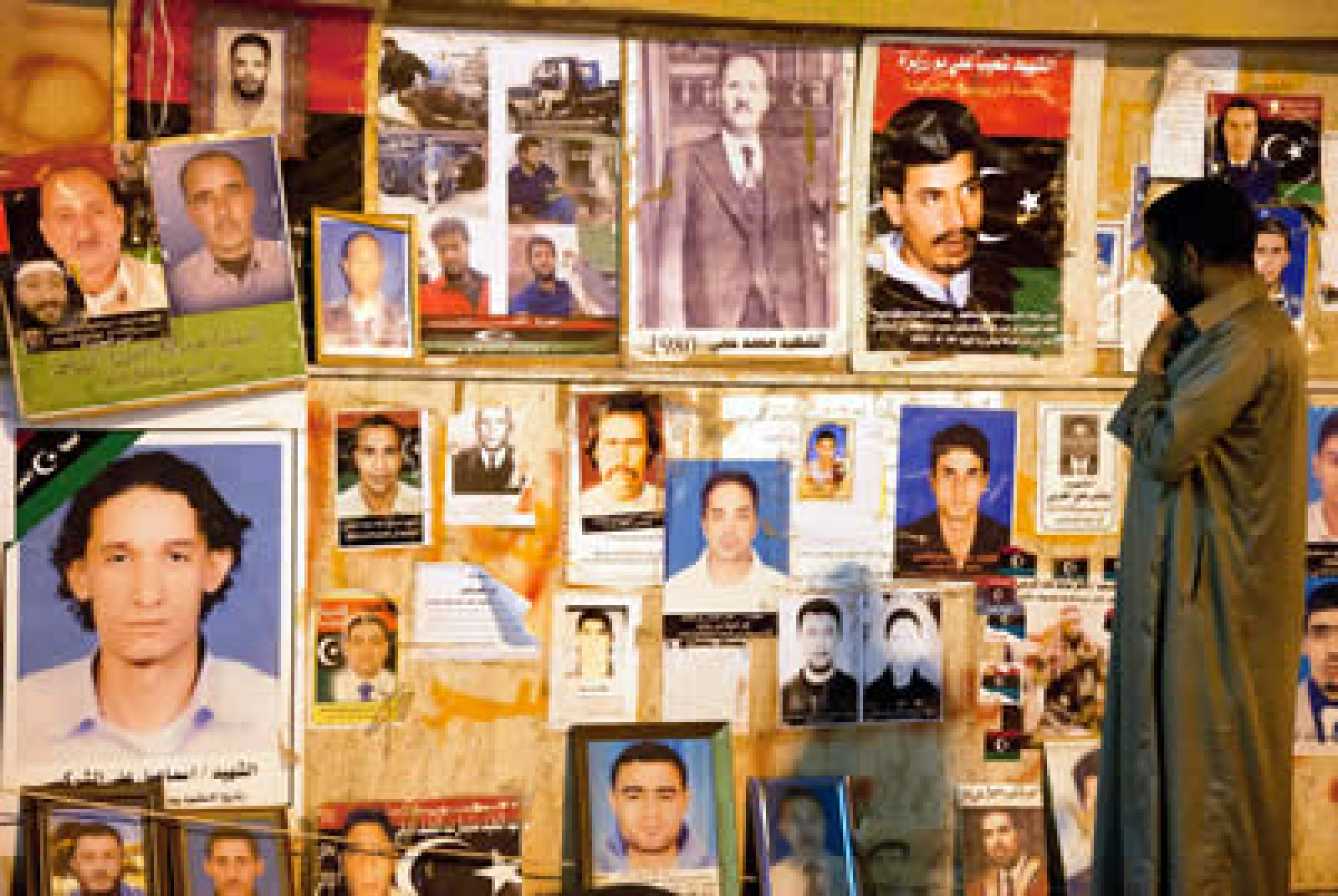

Pictured above: On one wall of Tahrir Square in Benghazi people leave pictures of those who died during Gaddafi’s reign, including the uprising which began in February. All photos by Maroun Sfeir, resident program officer in Egypt.

Published May 13, 2011