Success Story

Democracy Survey Shows Opportunities, Ongoing Challenges for Political Participation in El Salvador

NDI recently published the El Salvador 2009 Benchmark Democracy Survey, which measures citizens’ democratic values and perceptions of democracy in their country. NDI also has administered similar surveys in Nicaragua and Guatemala.

The survey uncovered a number of unexpected attitudes among women and young people, which prompted NDI’s former country director for El Salvador, Alison Miranda, to think about new ways to increase Salvadorans’ levels of political and civic engagement.

What does the survey measure?

The survey measures people’s perceptions of how democracy is working or not working for them. It also measures values and captures how those surveyed perceive and interact with others. For example, do they trust people around them? Are they tolerant? Do they believe in equal rights?

The idea is to find people that are either facing barriers or are completely marginalized from civic and political life and figure out what is preventing them from participating in democratic society. In that way, the survey provides a different perspective from most surveys: it doesn’t only focus on who is participating and how but rather who cannot, but would like to.

How is the survey conducted?

We worked with local partners in El Salvador, just as we did in Nicaragua and Guatemala. The survey is pretty extensive and is more like a conversation than a typical survey, so it’s important that local people do the interviews. We get the data back and do an initial run of the findings, and then we hold focus groups. We try to target the groups that we feel are most disadvantaged according to the data. We present the data to them and say “How does this look to you? Does this ring true? Does this track to your life?” Then we brainstorm with them how to address these barriers.

What were the main findings? Were there any findings that surprised you or went against conventional wisdom?

The perception among national and international analysts is that El Salvador has been able to develop economically and democratically more than its counterparts in the region. It doesn’t face the same levels of extreme poverty that Honduras or Nicaragua face. There were relatively well-run and peaceful elections in January and March 2009 and a peaceful transition from the right-leaning party that had governed for 20 years to the principal left-leaning, former guerilla party. But the data revealed that certain sectors are being left out of the process. I think what the survey revealed is that while the peaceful transition to democracy has been achieved, it doesn’t mean the consolidation process has come to an end. There’s still work to be done in El Salvador.

The conventional wisdom is that youth are not interested or apathetic. But in El Salvador, youth demonstrate similar levels of political knowledge as adults; however, they are far more interested in engaging (61.8 percent of youth were interested in politics, compared to 48.7 percent for adults). Young people expressed a real sense of frustration about the voting process, such as the relatively cumbersome process for obtaining the citizen ID card (DUI, for its Spanish acronym) required to vote, and access to birth certificates needed to request a DUI.

Women’s disengagement and absence from democratic life was also particularly shocking. Historically, they vote at lower levels than men. But I expected the survey to show that women were the ones participating in their communities – going to the parent-teacher association meetings or building community gardens, but they’re not. In fact, it’s young men who are doing that. There’s also conventional wisdom that says women aren’t engaged because they don’t have access to education, but according to the data, women are not participating regardless of their education level. Only 23.7 percent of women reported high levels of civic engagement in their communities, compared to 39.8 percent for men. The gender gap is even more pronounced for political engagement: 22.1 percent of men reported being politically active compared to only 7.9 percent of women.

Another surprising finding was an extremely high percentage of people – more than 60 percent – who said they would be willing to approach their local government to resolve an issue in their community, but that rarely ever happens (only 14.8 percent of people said they had done so). So what is going to push them from considering it, to actually going to the municipal council and voicing their problems?

What are some of the factors keeping women and youth from participating in democratic life?

In both instances, there are motivational and institutional barriers. Motivational is: “It’s too costly for me to do this. I don’t have time. I’m working two or three jobs and I can’t get time off.” There are pretty high motivational barriers facing all demographic sectors we looked at. Institutional barriers primarily affect young people – they have trouble getting their citizen ID card or obtaining a birth certificate. Young people are twice as likely as the average population to not have a birth certificate. Youth cited “lack of a DUI” and “not on the voter’s list” as the two principal reasons for not voting in the March 2009 Presidential election, whereas adults mainly cited “lack of interest”. Through the focus groups, women cited the issues of security, violence and crime keeping women and girls in their homes and out of public life.

Now that you’ve identified these barriers and the demographics they affect, what can be done to change them?

Some of the values we track in the survey are cynicism and interpersonal trust issues. So the survey provides a better sense of who doesn’t trust anybody around them and who is the most cynical, who believes that the government wouldn’t do anything for them – and these sectors could be targeted to encourage greater engagement and to open up different ways of participating.

For institutional barriers, like not being able to obtain a birth certificate, one option is to work with the entities in charge of handling birth certificates to identify a solution. Conducting an independent audit of the voter registry and other citizen data sources that feed the registry would be an important step to better target where the disconnect is between citizens who want to vote but who are not on the voter registry.

But for motivational issues, it is clear that one issue in El Salvador is the need to create a safer environment where people can feel confident that they can go out of their homes and not face negative consequences for advocating putting up a wall to keep the river from overflowing into the kids’ school, or whatever the issue is. It is necessary to organize and build that personal trust, and that starts at a grassroots level.

What are the next steps to ensure that positive change comes from the survey?

One step is to organize smaller round table discussions, putting together, for example, people from the Ministry of Social Inclusion and the Committee for Equality and presenting them with this information in a way that challenges conventional wisdom about women and youth in the democratic process. The goal is to create synergies with different groups that are probably operating pretty independently, to really challenge people. What would they do about this? What are the solutions? What are the solutions to the security situation? How do you get people to participate in their communities through formal mechanisms and processes? How do you open channels to get youth to vote?

Also, political parties should take a real interest in these results. Political parties have not been reaching out to large sectors of the population that could be winning elections for them. But they could really be targeting messages to these sectors, particularly youth, and engaging them either as rank and file members or at least figuring out what their needs are and mobilizing them.

Unfortunately, NDI closed its office in El Salvador at the end of 2009, but we’re hoping that this benchmark survey and the findings in the report can serve as a tool for local elected officials, political parties and civil society groups to engage more women and youth. I hope that those groups will look at this data to include more people into the democratic process by lowering the institutional and motivational barriers to participation.

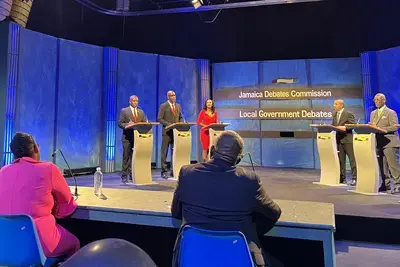

Pictured Above: Alison Miranda, NDI’s former country director

Published January 26, 2010