Success Story

Mexican Civic Groups Bring Public Security Concerns to Politicians

Organized crime and an exponential growth in violence have generated serious challenges to democratic institutions in Mexico. Despite concerted efforts by the Mexican government against organized crime, many citizens, particularly in border cities, feel that the government is not providing even basic protection, and they have begun to speak out individually and collectively about their concerns.

Civil society in Mexico has not traditionally taken a strong advocacy role. Many groups provide community services, do charity work, and serve as professional associations, but few advocate on public policy. There has also been historic mutual suspicion between public officials and civil society. The civic groups want to avoid being co-opted by politicians, while parties and politicians feel that civic groups are often unrealistic in their demands and are reluctant to engage civil society proactively.

Julian Quibell, who directs NDI’s programs in Mexico, sat down for an interview on how NDI is bringing these two groups together to show how collaborative dialogue can help deal with these concerns and strengthen the capacity of democratic institutions to address priority issues like citizen insecurity.

How exactly is NDI helping this dialogue?

NDI is supporting civic groups in their effort to communicate policy preferences and encouraging them to follow through with repeated contact with policymakers until action is taken by their local government. We are also working with the local governments to help them see the benefits of discussing policy with civic groups and getting a commitment from groups that have traditionally been shut out of the conversation to work with government to achieve solutions.

Where are we doing this?

NDI is working in Ciudad Juarez, just across the border from El Paso, Texas, and Tijuana, right across the border from San Diego, which are two of the more violent and crime-ridden cities in Mexico. In both cities, NDI brought together diverse organizations – like human rights groups, a committee of doctors and experts from universities – to present a united front in discussing their concerns on security policy. They have safety in numbers. They realize that if only one group sticks its neck out and talks about public security, they are much more likely to be a target for retribution from organized crime. So the groups are coming together to leverage their voices and speak out more forcefully about their concerns.

What was your message to convince both sides it would be a worthwhile exercise?

Taking advantage of the attention focused on the recent mayoral election, to the civic groups we said, “We’re going to organize round table discussions with mayoral candidates between now and when the campaign ends [for the July 2010 election]. All you need to do is create a series of questions that you’d like to ask the candidates because it is going to be a non-confrontational and non-debate format. It’s going to be you guys sitting around a table, as equals, and you’re going to ask the questions to get a better idea of what the candidates’ preferences are, what their strengths are and what their weaknesses are in the security area.”

For the candidates, NDI played the role of a broker, an independent third party, that brought them to the table and that could, to a certain degree, guarantee that these groups weren’t going to just start throwing stones. Because that is one of the reasons for the reluctance of many candidates and party officials and some government officials in Mexico to do more to reach out to civic groups – their perception often is that they get verbally attacked and criticized as a matter of reflex, not considered discussion, and don’t see the value of building relationships with civil society.

How did the civic groups get on the same page ahead of the roundtable discussions?

In the two months before the elections, the groups came together to develop questions and analyze the security situation. They subdivided their questions around certain themes. For example, they asked, “What criteria are you going to use to choose your public security director? What sorts of programs will you use to reform the way police are doing business now to ensure they are not corrupted by organized crime? What sorts of education programs or cultural programs do you envision supporting during your administration?”

Are the topics in the discussions all about public security?

Yes, it’s all public security related, but the groups have defined public security policy broadly. For example, if a root cause of the recent increase in crime is because many young people have dropped out of school and are unemployed, we need to think about how to expand the education opportunities for these young people. So discussion might include ways to keep kids occupied in something that is productive and away from organized crime bosses who use them as foot soldiers. We encourage them to take the long-term perspective and that tends to generate discussion of the prevention view, so it’s not just police and guns and more enforcement, but also a view on how the community can better serve people who are involved in those activities or prevent folks who may fall into them.

How did the first round of dialogue differ from the second?

We did some focus groups in Tijuana between the first and second rounds of discussions with the candidates. We asked citizens from a broad spectrum of the population in Tijuana about their perception of ongoing crime-prevention programs implemented by the municipal government. The broad strokes of the findings were that the average citizen did not know anything about those programs and, in many cases, didn’t even know they existed, and the programs they did know about they did not rate highly. So there was solid information that these civic groups could bring to the second round of discussions with the candidates and say, “This is not just our concern. There is a generalized perception that the security polices to prevent crimes aren’t working, and we’re hoping that if you win, your administration can help.”

So, we’re hoping to continue to motivate them to do that, to base their arguments on something beyond their anecdotal experience or what they have heard on a radio show and get some solid data for their arguments for policy preferences.

What was the reaction after the talks?

We got great responses from the candidates. They said things like, “This is the first time we’ve ever sat down in this format and we loved the fact that this was brokered and that there was an order to it.” They informed us that the questions from the civic groups were well-thought through and that the candidates were able to express views for at least a couple of minutes on each of these issues.

The civic groups were very happy with the methodology because this was the first time they had been able to successfully convene a meeting with a current or potential public officials, as opposed to being convened by public officials, which is what normally happens. The meetings changed the balance of power in that sense.

What do you think was the benefit of this?

I think the success story is that you had these groups that were previously working individually on public security and a range of other issues that are now working together. They have now seen the benefits of working together; they have seen the benefits of sitting down directly with the candidates and subsequently they have already expressed interest in sitting down with elected officials to continue this conversation. The civil society groups are taking a long-term perspective and understanding that this was the first phase of work they need to do over the next three years of the administration to document and argue their case for specific polices and to look for opportunities that bring them to the table and give them some voice in the decision-making process

On the side of the candidates, I think that they realized that although this wasn’t a huge campaign rally, it was a forum where they were able to reach people in the community who have influence over other voters by virtue of the work they do.

What kind of follow up is planned now that the elections are over?

NDI is going to implement focused planning retreats with civic groups in both cities so that they can prioritize proposals to present to the now elected officials, who do not take office in Tijuana until October and Ciudad Juarez in December. So the groups have considerable time to develop these proposals and develop initial working relationships with the mayors-elect. We are also working in a similar vein in the state of Mexico, but there with state legislators, who have requested NDI strategic planning support and have begun to develop new outreach activities to engage civic groups in legislative processes.

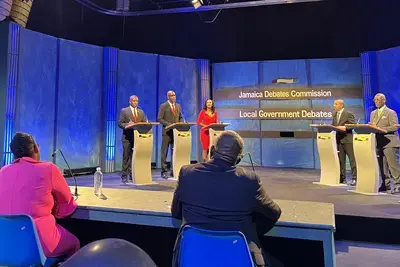

Pictured Above: Julian Quibell, NDI’s resident senior program manager in Mexico

Published September 13, 2010