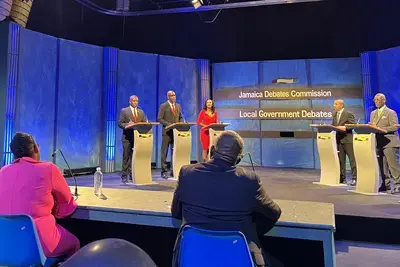

Party representatives from Guatemala, El Salvador and Honduras gather to discuss opportunities and challenges for reforms to internal candidate selection processes in the Northern Triangle.

Success Story

Supporting Candidate Vetting in Central America’s Northern Triangle

In Latin America and around the world, citizens are increasingly wary of political parties. In Central America, this is particularly acute where recurring party scandals involving money in politics are compounded by growing insecurity, corruption and impunity, all of which have led to increased rates of migration. Of all the democratic institutions in Latin America, citizens have the least confidence in political parties and parliaments, with a mere 13 percent of citizens expressing any level of trust in political parties and 21 percent in parliaments. In the three countries of the Northern Triangle – El Salvador, Guatemala and Honduras – these numbers can dip as low as six and 10 percent. To help political parties identify approaches to address the lack of confidence that these institutions face in the region, NDI commissioned a survey of practices in Latin America for choosing legislative candidates.

A critical element of party transparency includes strengthening internal party candidate vetting in order to better identify and select high-quality nominees. Kevin Casas-Zamora, former Costa Rican second vice president and minister of national planning, took the lead in developing the study. Titled Legislative Candidate Vetting Mechanisms in Latin America, the publication provides case studies on how parties in Latin America have explored and implemented candidate vetting processes, which could be a useful tool for parties to identify approaches to improve transparency within their ranks. The study also provides civil society and journalists with examples of practices that can be adopted to advance party transparency and accountability.

NDI convened 36 civil society members, journalists and party representatives from 14 political groups across the subregion to formally present the study in July 2019. Participants discussed opportunities and challenges for reforms to internal candidate selection processes in parties and shared experiences of citizen-led initiatives in Latin America to increase candidate selection oversight through normative and institutional reforms, judicial and electoral channels and the press.

Forum participant Natalia Paniagua, a youth member of the Nuestro Tiempo party in El Salvador and member of the Salvadoran Electoral Review Board (Junta de Vigilancia Electoral), emphasized the importance of implementing vetting mechanisms to ensure more transparent and accountable political parties. Part of Paniagua’s interest in learning more about vetting mechanisms stems from her fight for improved transparency in candidate and campaign financing in her country: “[A] major challenge for political parties is financing. It is expensive to run political campaigns, and organized crime has infiltrated politics, in some cases through campaign finance,” Paniagua said.

Participants were exposed to candidate vetting experiences from other countries, including best practices to promote party transparency. For example, Ariel Ávila, a civil society representative from the Peace and Reconciliation Foundation (Fundación Paz y Reconciliación, Pares) in Colombia, presented a case study on the benefits of strengthened candidate vetting procedures to disqualify legislative candidates with ties to illegal groups or funds that could jeopardize the party’s credibility and ability to win elections.“Political parties in El Salvador can learn from candidate vetting mechanisms abroad,” said Paniagua.

Examples of candidate vetting mechanisms include the “one-stop service desk” (Ventanilla Única) and the “empty seat” (Silla Vacia) legislation from Colombia, which was adopted a decade ago. The “one stop service desk” created a nonpartisan governmental body with the capacity to conduct in-depth background checks on candidates seeking a party nomination, while the “empty seat” legislation incentivizes due diligence by party authorities by penalizing elected representatives convicted of serious crimes with the loss of their seat in Congress and prohibiting the party from nominating a replacement candidate.

“Colombian legislation underscores party responsibility in the endorsement of candidates to elected office…[and creates] the figure of the party ombudsman who is responsible for reviewing aspiring candidates’ history,” Paniagua said. She also sees the “one-stop service desk” as a useful and replicable legislative tool, ”which serves as a unified consulting mechanism and centralized information bank on the personal backgrounds of aspiring candidates.”

Reform-minded party representatives recognized the importance of introducing the topic of candidate vetting to their parties and suggested that it would be easier to discuss this topic as part of multi-party conversations. Civic groups discussed actions they could take to advance the adoption of improved standards in party selection processes, such as advocacy campaigns to pressure parties to select ethical and transparent candidates. Other potential actions include dialogue sessions with parties to collaborate on candidate selection processes, legislation to regulate and monitor political party financing, civil-society endorsed party candidates and monitoring efforts on internal candidate selection processes, for example during internal primary elections.

With the publication of the study, political party leaders have begun to reach out to NDI to learn more about candidate vetting practices. In October 2019, the Institute facilitated a regional learning exchange between the ombudsperson of the Colombian Liberal Party and officials from the Mexican National Electoral Institute (Instituto Nacional Electoral, INE) as well as interested political parties, to share best practices on candidate vetting. NDI is also supporting civic partners in the Northern Triangle to advocate for more transparent and inclusive candidate selection processes. NDI will continue facilitating collaboration among civil society and party leaders to strengthen mechanisms that generate greater public trust in democratic institutions like political parties.